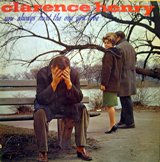

This week’s choice is an old standard made famous by a rockabilly singer who earned his nickname from the way he sang. That man is Clarence Frogman Henry.

Clarence was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in March 1937 and when he was 11 his family moved west to the Algiers area of the city when they were unable to afford the rent. He was one of six children and he recalled when he was growing up, “My daddy played all kinds of string instruments, as well as the harmonica and piano – I don’t care what, my daddy played it. My mamma kept us in the church, so we had to go to Sunday School.” He listened to a lot of Fats Domino and Professor Longhair – so much so that he used to imitate them at school – and came to love the piano. “When I was 8 years old I asked my mama to send me to piano lessons because she’s sent my sister and she didn’t like it. So I started going and learned the fundamentals. My style I taught myself.” His mamma was keen for him to learn the blues, so to please her he did, but when she left the house for work he then played the boogie-woogie that he loved.

His school teacher put a band together with a local r&b singer called Bobby Mitchell, they were called The Toppers and Clarence was with them for about three years. He also learned the trombone and alternated between that and the piano. He graduated in 1955 and the following year got a job in the Fatman club working four hours a night for $5. He was making a name for himself because he then went to work at Bill’s Chicken Shack for a little more money and moved onto the Old Joy piano lounge where he earned over $50 a week. Next he got a job in a club called the Brass Rail where Paul Gayten, the A&R man for Leonard Chess (of Chess records) was also playing. “I started singing a song called Ain’t Got No Home and I played it for Paul who sent it up to Leonard Chess. Leonard then came down to hear it,” Henry said, the song was a novelty song and was the first occasion that he showcased his frog-croaking voice which thus earned him his nickname. He also sang part of it in a high voice which sounded female. Henry explained why, “Shirley and Lee were from New Orleans and were hot during that time. I didn’t have a female singer in the band, so I had to switch my voice like a girl.” And why the frog sound? “How I do the frog sound I don’t know. On the West Bank, Algiers, you had the alligators and frogs which I used to imitate in school, to scare the girls!” He had written a song called Lonely Tramp before Ain’t Got No Home and used to perform frog and female parts on that too. “When Leonard heard it he told Paul to break it up into different parts with the girl and the frog. Henry spent 1957 touring the US, especially New York, Washington DC and Baltimore where he shared a stage with the likes of former Drifters lead singer Clyde McPhatter and Roy Hamilton.

Gayten, along with Bobby Charles, the man who wrote and recorded the original version of See You Later Alligator, wrote But I Do, or sometimes credited as (I Don’t Know Why I Love) But I Do for Henry and he rewarded them with a top five hit on both sides of the Atlantic. Then came the follow-up; “Back in those days you had to get a follow-up to your hit,” Henry recalled, “they sent me a dub and I was supposed to record I’m A Fool to Care but some kinda way, Joe Barry came out with it before I did. So we went to Chicago and Allen Toussaint, who was the arranger for my session, and I were going through a lot of songs and we came up with this Ink Spots song called You Always Hurt the One You Love and cut it.” The song was written by both Allan Roberts and Doris Fisher in 1944 and originally recorded by the Mills Brothers the same year. Many people covered it including a parody version by Spike Jones in 1946 and then Connie Francis, who had the first UK hit in December 1958, Maureen Evens in 1959 and Fats Domino in 1960. The Ink Spots version, that Henry heard, was from 1957. Ringo Starr had a go at it in 1970, Willie Nelson in 1994 and Michael Buble in 2002.

Allan Roberts was a New York-born musician and songwriter who had originally trained as an accountant. He then started playing piano in clubs around Broadway and began writing songs for the likes of Benny Goodman and Billie Holiday. In 1944 he met an aspiring songwriter called Doris Fisher, whose father was the Tin Pan Alley songwriter and music publisher Fred Fisher, and began working on songs together and You Always Hurt the One You Love their first big success. Together they wrote many songs that were recorded by Perry Como, The Andrew Sisters, Ella Fitzgerald and Marilyn Monroe. Their most successful UK hit was That Ole Devil Called Love which was first recorded by Billie Holiday in 1944 and a number two hit in 1985 for Alison Moyet.

Henry’s follow-up was the double A-sided hit Lonely Street and Why Can’t You – the latter being written by Bobby Charles. “He (Charles) was from Abbeville and he was doing most of the writing for me,” Henry reiterated, “I loved his style. Bobby wrote songs that appealed to me, I could feel them. I liked Country & Western the way Bobby wrote it. Allen Toussaint changed it into a pop music feel but Bobby was a great, great writer. I’ll never forget him for what he did for my career. I admire him.” The song just missed the top 40 and was Henry’s last hit.

So what happened next? “When the bookings went down, I worked on Bourbon St and then a disc jockey on a radio talk show called me saying he would use Ain’t Got No Home for his homeless show and everything started happening for me again. There was over 29 years of royalties I didn’t get, so I got a lawyer who contacted MCA and they gave me five years of back royalties and from then on I started getting the royalties.” In 2005 Henry was inducted in the Delta Music and Rockabilly Halls of Fame and two years later inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.

As for the songwriters; Roberts died in Los Angeles in 1966, at the age of 60 and Fisher married a real estate developer in 1947 and then retired from the entertainment world. After raising two children she became an interior designer as well as an antique furniture collector. The couple divorced in the late sixties and she moved back to California to set up a kitchenware retail business. She died in January 2003 aged 87.