Richard Adams, in 1972, wrote his first book Watership Down while he was working at the Department of the Environment. It depicted a colony of rabbits, who are forced to move from their warren by building developments. Unlike many children’s books, Adams did not endow them with human characteristics and took great pains to treat life in the warren seriously: in short, they behaved like rabbits. The stand-out song went on to be the best-selling single of 1979, but how did it come about and, more importantly, what did the author think of the song?

The story told of a small group of rabbits who had to get out of the warren they lived in because it was to be built upon and therefore they were not happy bunnies. The book tells of how they find their new home and all the trials, tribulations and challenges they faced. Unbelievably, 13 different publishers turned it down before being accepted by Rex Collings Ltd. In 1974, work began on an animated film based on that furry tale.

There was much speculation as to how the book could be filmed and, after several years in the making, an animated film was released in 1979. When Mike Batt heard that an animated feature was being produced, he wrote and submitted many songs to the director. John Hurt’s voice was used for Hazel and Richard Briers’ for Fiver, whilst Joss Ackland was the Black Rabbit and Sir Ralph Richardson the Chief. Mike Batt was a big fan of the novel and desperately wanted to write the score, but the work went to Angela Morley (previously known as Wally Stott) and Malcolm Williamson. Mike kept submitting ideas for songs.

Watership Down director, Martin Rosen, gave Batt a brief and said he wanted a song about death. Those words did not come easily, “I remember coming home and thinking, ‘wow, how do you write a song about death without it seeming ridiculously dark or totally stupid?'” recalled Batt in an interview with Liam Allen. “It was then that I started to think, ‘well it’s going to be a song about wondering and not knowing’ Therefore, the opening words, ‘is it a kind of dream?’ came into my mind as I was sitting playing at the piano. I sang, ‘is it a kind of dream’, and then that minor thing of, ‘floating out on the tide’. I realised I was on to something because you start singing it and you’re so choked up you can’t carry on.”

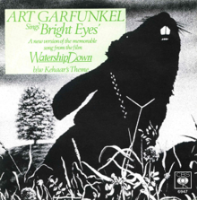

He submitted the song and then recalled, “They didn’t initially want to use Bright Eyes, but then Over the Rainbow was almost taken out of The Wizard of Oz. I had two songs that were dropped, so I then recorded Run like the Wind with Barbara Dickson and Losing Your Way in the Rain with Colin Blunstone. I told the producers that Art Garfunkel would be ideal for Bright Eyes and within a week, there he was, in my home in Surbiton, routining the song.” Eventually Bright Eyes was selected.

Art Garfunkel recalled his thoughts after being sent the original demo, “It knocked me out. I knew my own tone of voice has a quasi-religious pop element to it and I knew that I can create goose bumps with this mysterious enquiry into ‘what is this life and what is death for all of us? So it’s a wonderfully large, philosophical set of words.”

The song was released in March 1979 and went to number one where it stayed for six weeks. It went on to sell over a million copies and won the hearts of the nation, but one person who was not impressed was Richard Adams. Mike Batt told my 1000 UK Number One Hits co-author, Spencer Leigh, “I was watching Wogan and he asked Richard Adams what he thought of the film. He said that he hated Bright Eyes. He based his dislike on the assumption that it was wrong factually. He said it was about a dead rabbit – well, if he reads his own book, he’ll realise that the song is sung and thought by Fiver at a time when he thinks Hazel is dead. The point is that the other rabbit thought he was dead.”

Mike Batt looked back on the recording remembering, “It was one of the most difficult sessions I’ve ever been involved in, we even just argued over the way it should be sung and everything.” There was certainly some tension, “At the heart of the tension was a battle of wills over a duff guitar note. We did this great take which everyone loved including Art and yet there was one note, just one little slip. I told Art Garfunkel that, with a 60-piece orchestra waiting to come into the studio to record, I would simply ask the guitarist to come back the next morning to drop that note in. Art said ‘No, I don’t think we should do that, I think we should get it right now’,” Batt added.

Then another problem arose. Goddard Lieberson, the head of Columbia records and exec producer of the film told Batt he didn’t like the string arrangement. “I thought ‘how rude'”, Batt said, “that’s all right, I’ll go then, I’ll take my song and you can get someone else to write a song. I walked out through the orchestra with my score in my hand and I drove off in my car.” Thankfully, he was persuaded by the film’s director Martin Rosen to return and carry on and he could do it on his own terms.

When it was finished, Mike and Art listened back and realised they had made a hit, “all the tension and distrust had suddenly ebbed away”, Batt added. As soon as the song hit number one in the UK, Art called Mike and said, “Mike, I just wanted to say thanks and to share with you that we did so well with the record.”

There is a brilliant scene in Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, where Gromit is hesitantly waiting for the Were-Rabbit to pop out, so in the meantime turns the radio on and hears a clip of Bright Eyes and quickly turns it off looking horrified.