The 1960s was a decade that brought many protest songs, usually about war and, over the last five decades, surely the Vietnam War must lay claim to the most, either by subject or inspiration. We Gotta Get Outta This Place (Animals), Feel Like I’m Fixin To Die Rag (Country Joe McDonald & The Fish), 7 O’clock News (Simon and Garfunkel), Gimme Shelter (Rolling Stones), Fortunate Son (Creedence Clearwater Revival), What’s Going On (Marvin Gaye) and 19 (Paul Hardcastle) are all contenders plus there are many others that became associated with Vietnam, War (Edwin Starr), Green Green Grass of Home and The Letter by the Box Tops to name just a small handful. This week’s suggestion is not about Vietnam at all, but because it became it big hit during the conflict, many assumed its subject matter was. The story, however, is a true one, and involves a completely different war.

Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town was written by the country singer Mel Tillis who was born Lonnie Tillis in Tampa, Florida in 1932 and after serving in the Air Force in the mid-fifties, he returned to Florida and took a job working for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad company. This allowed him free travel which he used extensively and because he had an interest in country music, he used the perk to visit Nashville where he auditioned as a songwriter for Wesley Rose of the publishing company Acuff Rose. He also tried his hand at acting and appeared in Smokey & The Bandit II and Murder in Music City among others. He formed a band called The Statesiders and between 1958 and 1988 put 68 hits on the US Country Chart, some solo and some with the band. It included six number ones and three number twos. As a writer, he co-wrote Brenda Lee’s 1961 hit Emotions and Tom Jones’ 1967 hit Detroit City.

The song tells the story of a wounded war veteran who’s ‘lady friend’ as it’s not stated as to whether they were married or not, carried on having her fun and seeing other men whilst he was stuck at home unable to move. “Ruby… is a real life narrative about a soldier coming home from World War II in 1947 to Palm Beach County, Florida,” Mel Tillis once revealed. “The soldier brought along with him a pretty little English woman he called Ruby, his war bride from England, one of the nurses that helped to bring him around to somewhat of a life. He had recurring problems from war wounds and was confined mostly to a wheelchair. He’d get drunk and accuse Ruby of everything under the sun. Having stood as much as she could, Ruby and the soldier eventually divorced, and she moved on.” There is a line in the song, ‘It wasn’t me that started that old crazy Asian war’ which is where people put two and two together, but it could also have about the Korean War which raged from 1950 to 1953. There is a rumour that Tillis did, at one time, change the lyric to fit what people thought.

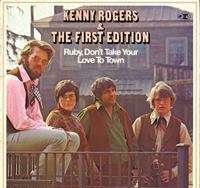

Tillis recorded the song first in 1967 on his album Life Turned Her That Way, the cover versions came quickly from Waylon Jennings, Roger Miller, Bobby Goldsboro and Johnny Darrell who all had a go in the same year as Tillis but none had any real success with it. There is a story of how Kenny Rogers, with his band The First Edition got hold of it, which, as Tillis recalled, “Kenny was in Los Angeles recording their Something’s Burning album, and the way I heard it, they had 15 minutes left on the clock. The producer, Jimmy Bowen, came out of the control room and handed Ruby to Kenny. And you know the rest.” Kenny recorded it similarly to the Roger Miller version and suggested putting drums on the beginning and the end. It gave the song a more dramatic effect and he advised the tambourine player, Thelma Camacho, to play heavy and the same with the guitarist. The other stand out feature is that Kenny narrates it more than sings it. Later versions came from the indie band Cake in 2005, the Killers in 2007 and there was even an attempt by Leonard Nimoy from Star Trek who even sings it rather than narrates.

Kenny Rogers’ version was released in 1969 and went to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart and number two in the UK where it spent five weeks behind Two Little Boys, which I know sounds wrong! Many assumed Kenny wrote it and began criticising its content about a man who can’t move because his legs are bent and paralysed and then saying that if he could move, he’d get his gun and put Ruby in the ground. In 1970, Rogers gave an interview to Beat Instrumental magazine saying, “Look, we don’t see ourselves as politicians, even if a lot of pop groups think they are in the running for a Presidential nomination. We are there, primarily, to entertain. Now if we can entertain by providing thought-provoking songs, then that’s all to the good. But the guys who said Ruby was about Vietnam were way off target – it was about Korea. But whatever the message, and however you interpret it, fact is that we wouldn’t have looked at it if it hadn’t been a g`zod song. Just wanna make good records, that’s all.” What probably made things worse was when Mel or Kenny played live, many would clap and singalong in a happy fashion which clearly upset anyone closer to the subject matter.

It seems Ruby was chosen as it was a popular name at the time especially in song. There was a film in 1952 called Ruby Gentry (which Roberta Lee Streeter took as a surname to become Bobbie Gentry) and Ray Charles recorded the theme and called it Ruby which became the follow-up to Georgia On My Mind in 1960. There was Ruby Baby, by the Drifters, Ruby Ann by Marty Robbins and Ruby Tuesday by the Rolling Stones.

Tillis was clearly a conscience songwriter, he ends the song with the line, ‘Ruby….for God’s sakes turn around’ leaving the listener to think she’s just walked away. Its real story is far sadder than that, He once answered the question as to what happened to the real life couple who inspired the song, to which he revealed, “He divorced Ruby and married someone else. The ending to this story is that the guy killed himself and his third wife. Very sad.” Even Tillis’s wife said, “it was too sad, too bleak and too morbid. A skilled songwriter leaves the ending uncertain” Maybe if this had been a more known fact at the time, the audiences wouldn’t sing and clap in their cheery, jovial fashion, but they didn’t.